17. Mai 1942

| GEO & MIL INFO | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Christishche Forest | ||||

| on 18th probably to “Grünpunkt 100”[1] | ||||

| 17–19 May Operation Fridericus Author is mortar platoon leader in 4th/477, CoyLdr: Max Müller[2] | ||||

At midnight the marching order comes. The platoons get into order and then the column leaves the village. We first follow the dirt road that leads to the forester’s lodge. On the way, some tanks overtake us. Their clumsy shadows rumble past us.

The forefront has reached a corner of the forest. A few figures emerge from the shadows of the trees: Our guides. We approach the egress positions. The column splits into individual shorter queues that disperse in different directions. Now the darkness of the forest has swallowed them. You can no longer hear a loud word, only whispered instructions, the clatter of a mess kit, the crack of a dry branch. It is not always as silent as it should be. In the stillness of the night, some noises sound overly clear, and suppressed curses then always rain down on the culprit.

The queue has broken up into individual groups that disappear into ditches and earth bunkers. It is our old defensive line, but now it is packed with attack troops. The forest has again wrapped itself in deep silence. It sleeps towards a new, splendid May day. A sunny day with blue skies and young, fresh green forest; a day when all creation breathes new, young life.

I stand in the ditch between our men and look up.

The new day begins to dawn. The dark tops of the trees already stand out a little against the night-blue sky. Some branches sway gently with whispering leaves. The ground is still quiet. The Russians over there are not stirring. They are probably waiting for us. We are waiting too. In the trenches the storm troopers squat man next to man. Cheek by jowl we sit close to each other. In the pallid light of the approaching morning, I see their matte shining steel helmets like a huge grey string of pearls. Here and there a helmet moves. No one speaks. It is the calm before the storm. The men sit in silence. Everyone is busy with himself. I too feel the tension of nerves again. The teeth vibrate when you don’t bite them together. This waiting is awful. The order to attack is almost a relief. Only this damned jungle! This is ideal terrain for the Ivan again.

17 May 42 – 3 o’clock in the morning.[6] A few muffled discharges behind us and already a truly animalistic howl rises above the treetops. Rising and falling howls and yowls fill the air, and then the earth trembles under the force of numerous explosions. Our Nebelwerfers are firing! The crash of the impacts drowns out the breaking and bursting of the trees. New howls mingle with the inferno. They penetrate to the marrow. Coming from great heights, it howls down. The sirens of our dive bombers! With indescribable force they hammer their heavy bombs into the forest in front of us. The earth bounces and the air pressure of the explosions lifts our steel helmets. For minutes this howling, crashing death rushes into the Russian positions. The forest drones and shakes. Our men have risen and look into the forest with burning eyes. White flares whiz through the treetops high into the air to show the Stukas the course of our line.

Now a signal: Attack! A wave of grey-green figures climbs out of the trench and penetrates the forest. Soon they have disappeared into the dense undergrowth. The bomb impacts have fallen silent. The first rifle shots fall. How bright and harmless they sound after the booming rumble of the bomb impacts! The infantry fight begins. Into the scattered fire of the rifle shots and the rattling of the machine guns, here and there the hurrah of the storming Germans flares up. The echo intensifies the storm cry and makes the forest reverberate with it. It sounds as if from a thousand throats - and yet there are only 300 of them!

Woodland combat! We push into the forest in wedges. The spearhead group consists of selected and proven fighters who are equipped with numerous special weapons: Assault rifles, rifle grenades, submachine guns, hand grenades and grenades that can be fired from flare guns.

The undergrowth has thinned out somewhat and disappeared completely in places. We are in the high forest, and soon we stand in front of the first defensive positions of the Russians. It is a several hundred metres long and three metres high tree barricade, from which we are met by heavy defensive fire. A really cursed situation. You can’t see any enemy, but it’s banging from all the gaps. Since the barrier may also be mined, we have to be careful. So we first take cover behind the trees and try to spot fire positions, machine gun nests and individual shooters. A bang, a muzzle flash, a movement betrays the enemy to us, and then we chase our bullets and bursts of fire across. But the Russian has better cover, and some of our comrades are hit. The quiet, sympathetic lieutenant from the forester’s lodge is badly wounded by a shot in the spinal cord. With a frighteningly pale face, he lies on the stretcher and his head hangs powerlessly to one side as the paramedics quickly carry him past me out of the firing zone. You can see that he is close to death. We have already gained some experience in this. You can tell if a person is dead or wounded by the position of the body or the position of the limbs. The same goes for the facial traits or the colour of the face.

There is a Soviet machine gun nest spotted behind the tree barrier. A private loads his flare gun with a rifle grenade, aims by eye and pulls the trigger. The “pineapple” grenade flies over to the enemy in a steep arc and falls vertically behind the tree barrier. It detonates with a crash in the middle of the machine gun nest. Direct hit!

There are always such unbelievable incidents. We call it happenstance. In reality, it’s probably fate. In this case, was it luck or efficiency on the part of the private? In any case, he is already wearing the EK I (Iron Cross 1st class).

To my right, there is a hard fight for a gap in the tree-barrier. A bomb had torn open a breach here. The wall is crooked. Our soldiers had worked their way up. After a fierce firefight, the first attackers had broken through. Others quickly followed, and now the red positions are being rolled up from the side. More and more new squads are pouring through the breach. The Russian can no longer hold on and begins to retreat in disintegrated heaps. His dead remain lying. We pursue the retreaters, but before that the private and I take a quick look at the downed machine gun nest. The machine gun has been knocked over. Next to it lies a dead man. Behind the gun lies the gunner with the back of his head ripped open. His face is on the ground and his brain hangs out of the broken skull.

The forest seems endless. Still we advance. From time to time with a roaring hurrah when individual enemy groups try to re-establish themselves. Sometimes just to demoralise the Ivan or to maintain acoustic contact with neighbouring companies in this confusing forest terrain.

In the meantime, the Soviets have moved off so quickly that nothing can be seen of them. But the forest is large and the Russians’ retreat is not yet a victory. With his sneaky fighting style, one must always expect surprises.

Suddenly, around noon, “Stop!” is ordered. The squads come to a halt. In such terrain, connections between units are easily broken, and this can lead to dangerous dissipation. So one stops to check the connections or, if necessary, to re-establish them. Then comes another command: “All-round defence!”. Why, what’s this!? We form a big circle and set up for all-round defence. Some soldiers shovel themselves a foxhole. Most have simply laid down on the ground and are resting. There we stand, feeling like we are alone. One company, a small lost bunch in the great sea of forest. Have we lost our way? Lost our direction? Lost contact with the enemy? Lost contact with our neighbours? Some soldiers come to me with similar thoughts. I go to Max Müller to find out about the situation. But even he, as the company leader, doesn’t know exactly what’s going on, but says everything is all right. Then we hear shouts and answers on the right in the forest. They are Germans. So there we have a connection.

I know that in combat it is not possible to tell every single soldier the battle situation. That is impossible and not always necessary. On the other hand, there is no doubt that this lack of information often leads to uncertainty and unwillingness on the part of the ordinary soldier and even gives rise to false orders on the part of the lower command level.

Suddenly a machine gun rattles off on the left. Short bursts of fire, excited shouts. I look in the direction and see single earth-brown figures scurrying through the bushes. Russians! I quickly gather a few men and go after them. They haven’t got far. Three of them lie bleeding in the grass. The machine machine gun bursts had got them. The others are hiding behind the trees. We soon reach them. I call on them to surrender. The “rooky vyerkh!”[7] has long been familiar to us. Four more men then come out from behind the trees. We briefly search the area and then head back. The Ivans had lost their way and were wandering around in the forest until they unfortunately ran into us. One of them is wearing a German steel helmet. This full-faced Ivan grins at me. Embarrassment or impudence? My nerves are still tense anyway, and anger seizes me. I turn my submachine gun around and bang it on Ivan’s head so that the shoulder rest bends slightly. The Russian hasn’t felt the blow through his steel helmet at all, because he continues to grin. Or did he notice that I suddenly hesitated. I remembered how easily this cheap SMG goes off. With this faulty design, the momentum of the blow would have been enough to set the recoil mechanism in motion by centrifugal force, and the shot would have been released automatically. I could have shot myself through my lack of restraint, because I had turned the SMG around and the muzzle was pointed at me. Subconsciously, I thanked the Lord God for his incomprehensible forbearance with me.

I visit the wounded Russians again. Two are already dead. The third is seriously wounded. He is sitting in the grass and propping himself up on the ground with both hands. I think about what to do with him. We can’t take him with us and obviously we can’t leave him behind. We can’t leave ourselves and we don’t know what the next few hours will bring.

Suddenly someone shouts, “Drop the guy!”. An impulsive, thoughtless shout. I hear it without actually thinking about it. In such nerve-racking situations as this forest battle, such a thoughtless exclamation can slip out, and one hears it just as thoughtlessly, without it penetrating one’s consciousness. Here, too, I don’t even realise that this exclamation is an invitation to murder. Who actually called out? a corporal? a sergeant who was standing nearby at the time? I see a Landser approach the wounded man. He holds the muzzle of his rifle to the Russian’s neck and pulls the trigger. A short bang. A jet of blood as thick as a finger shoots out of the Russian’s throat and gurgles into the grass. After a few seconds the Russian bends silently at the elbows, his head tilts slowly, and then his upper body sinks forward into the grass. He is dead.

The captured Iwans are immediately put to work digging foxholes.[8] Once again I am amazed at the speed with which these outdoorsmen can dig themselves into the earth. It is unbelievable!

Then the order sounds to continue the attack. We pass a second tree-barrier, which the Soviets have voluntarily abandoned. Very pleasant! Ahead of us now lies a wide hollow with very sparse trees. They are all tall, strong trees. A few stray horses graze carelessly in the hollow and are immediately used by paramedics to transport the wounded. We descend to the bottom and then veer off to the right. I realise that I am dog-tired.

The resistance of the Bolsheviks has seemingly completely collapsed. In their retreat they must have apparently become completely confused, because scattered groups of Red Army soldiers keep running into our arms. Since we no longer have any contact with the enemy, we form a column and march along a swathe as if on a practice march in the homeland. Two hundred metres in front of us two Soviet horsemen appear. They come around a corner and turn into our path. Like lightning, our marching column disappears into the bushes on the left and right, while a machine gunner throws himself into the middle of the path with his rifle and takes up a position. The riders saw us immediately, of course, but before they can turn their horses, the machine gun rattles off. A rider falls from his horse. By the time we reach the spot, the Russian is dead. His good horse had stopped beside him. A paramedic takes it away.

There is no end to the forest. However, it has become thinner so that we can see further. We march under the mighty old trees as if under the dome of a huge cathedral. Then word comes through that our point has encountered a Ratsch-Bum battery, which is being fiercely defended by the Russian artillerymen. The squads are quickly divided up for the attack, while rifle fire is already flaring up in front. Max Müller takes the lead. The accommodation bunkers were quickly overrun. The red artillerymen left their dead and wounded and retreated to their gun positions. I, as a mortarman, did not take part in the attack and stayed with the bunkers. A wounded Russian is sitting in front of one of the bunkers. He raises his hands in supplication. I exchange a few words with him, but I can’t help him. I descend into one of the bunkers. Apart from a few dead bodies, there was not much to see. On the cots lay a piece of clothing, a few of those sack-like bags that correspond to our knapsack. Inside the bags were some hard bread and lump sugar. Here and there a shirt or a towel. An unassuming people!

The infantry fire flares up more. The Russian battery is in an area of dense, man-high trees, while our soldiers have to crawl through sparse high forest. The Russians lie in their cover and shoot at every movement. We have casualties. Lieutenant Schröder, who had already behaved so foolhardily at the forester’s lodge, is of course right in front again. He had crawled within throwing distance of the Ivan, pulled a hand grenade out of the paddock and torn off the fuse. As he is about to throw, the hand grenade is hit by a Russian bullet and explodes in his hand. It tears off three fingers of his right hand and one finger of his left hand. Half numbed with shock, he has rolled to the back, where a man bandages him up. Then they lead him back, and now he lies here with me at the bunkers. I stay with him. He is still almost numb. The wound shock is over and he is getting pain. I try to comfort him and distract him a little, and he feels it with gratitude.

In the meantime, the battery has been captured. It is the one that always fired at us in Majaki. Max Müller proudly writes in chalk on the guns: “Captured by 4th/477 on 17 May 42”.

On we go. There is still no end to the forest. After a long march it finally gets lighter in front of us. We approach the edge of the forest. No sooner have our first squads reached it than they are met by fierce fire. We take cover to get a feel for the situation. I lie behind a tree about twenty metres into the forest, but I can easily see the terrain in front of me. In front of the edge of the forest is a hollow about four hundred metres wide, with a stream meandering through the bottom. The hollow is flat and only overgrown with grass. The opposite slope rises more sharply and is in places a steep slope about five metres high, behind which sprawls sparse scrub and coppice forest.[9] The whole edge of the steep slope over there is peppered with bunker and earth positions, which like fire-breathing dragons shower us with a hail of bullets. An almost ideal defensive position. The Russians’ third line of resistance: A whole chain of fortified fire positions on the edge of a five-metre-high steep slope, partly hidden by bushes. And in front of it, four hundred metres of completely free, open terrain without the slightest possibility of cover for the attacker. An attacker who has been fighting his way through an endless forest for twelve hours and is almost at the end of his tether. A damned situation, but we must get across.

In the meantime, our rifle companies have taken up positions in a broad front at the edge of the forest. Now we are pulling all available machine guns to the front. They are the only weapons at our disposal. We cannot use my mortars. The grenades would explode in the treetops as soon as they were fired, and we would be covered by our own shower of splinters. Pak and infantry guns could not be carried through the forest either.

Our heavy machine guns begin to return the enemy fire. Since it is impossible to destroy the fortified earth bunkers over there with machine-gun fire alone, the only option is to cover the embrasures of the bunkers with a hail of bullets in such a way that the Ivan cannot put his head up and therefore cannot fire in a targeted manner when our infantry attacks. That is exactly what we are doing now. Our rifle companies are preparing to charge. In wide-open order they step out of the forest onto the meadow ground and begin to cross it. Meanwhile, the air billows with the drumming continuous fire of the countless automatic weapons. No more individual shots can be heard, only the bright, rattling rise and fall of this seething infantry battle. For minutes the machine guns rattle on both sides. There is no pause, no let-up, no halt, but only the frantic hammering of the rapid-fire weapons like the endless rumbling rattle of hundreds of riveting hammers.[10] Fifteen minutes have already passed. With undiminished fury, the machine guns rattle as our infantrymen walk the shallow hollow of the valley. They are not in too much of a hurry. Under the cover of our furious fire, the enemy defences are not very strong or effective. Besides, they are probably tired too. They walk across in dispersed groups, at a wide distance from each other. The first squads are already across. The slope is not so steep here. The Landsers begin to climb up the slope to attack the red nests in close combat. To our right, the enemy defensive fire has clearly diminished. Some positions are being abandoned by the Russians as our soldiers approach. They have run out of ammunition or courage. They are certainly demoralised. No wonder, after today’s defeat. Then suddenly a Russian tank appears, rolls up to the escarpment, swings its barrel and blasts a shell into the widely dispersed swarms of our infantry. The men go on unconcerned. Again a black fountain splashes up between the Germans. A man falls, gets up again and walks on with a bleeding arm. A third shot tears new chunks of grass into the air, but the distances between the individual soldiers are so wide that the grenades burst ineffectively in the wide gaps between them. The Landsers do not even throw themselves to the ground. They stroll on calmly. After all they have already been through today, the tank banging leaves them completely cold. And they are certainly far too tired to throw themselves down and get up again every time.

I have often experienced this recklessness on the part of our soldiers during attacks. Be it fatigue or laziness. In any case, it is stronger than fear. But this carelessness has already cost us many unnecessary losses.

The tank turns around and disappears. The Reds’ resistance is crumbling. The mass of our companies has reached and climbed the slope over there. Now one bunker after the other is fought down with close combat weapons, conquered and occupied. The resistance of the Soviets is broken. Whoever of them could still run has fled.

A lull in the fighting occurred. Our machine-gun company had provided fire protection until then and is now waiting for the order to cross the hollow as well. We lie waiting at the edge of the forest. Two horsemen appear over there. They come from far to the left and seem completely clueless. (The confusion must have been indescribable on the Russian side today). In the glass I recognise an officer with his boy. They come down the slope and trot leisurely through the meadow towards our positions. They are still three hundred metres away and we want to let them approach quietly. Then a stupid machine gun goes off on our right. Way too early. The officer turns his horse and chases back, dashes up the slope and disappears. His boy, on the other hand, had immediately slid off his horse and thrown himself to the ground. When the machine gun stops, he rises and comes over to us with his hands up. Once here, he extends his hand to Max Müller in greeting. Max takes it and they both shake hands laughing. We don’t pass him off to the back, but keep him as a driver with our train. Ivan turns out to be quite a cunning slyboots, but he makes himself very useful and stays with the company for a very long time.

Our company is able to set off and crosses the hollow. It is late afternoon. For fourteen hours we have been fighting our way through the endless forest in oppressive heat. For fourteen hours I have neither eaten nor drunk. Now that the tension has subsided, hunger, thirst and tiredness are setting in. Yes, I am dog-tired, because I have not slept for two days and nights. But now I have to drink something first. There is a stream down there. The dark bottom of the stream is muddy and partly covered with creepers. The foot-deep water is somewhat murky and lazily washes over the corpse of a Red Army soldier. In places the stream bed is overgrown, and small pools of water stand on dark moorland. I hesitate to drink. So far in Russia I had drunk neither water nor raw milk. Even on the hottest days of the advance, I never drank my canteen full of coffee on the way, but saved most of it until the evening. But today it is empty. My thirst was too great and still is. And so I bend down and drink half disgusted, half refreshed of the tepid water.[11]

Our attack was successful all along the line. The entire Great Christishche Forest, which stretches almost to the Donets, is in our hands. By losing the forest, the Russians can also no longer hold the villages of Christishche, Siderovo and other places situated on the Donets. They evacuate the villages almost in flight, so that they fall into our hands almost without a fight. Thus we regained the old front on the Donets, which had been lost in the course of the winter.

In Christishche I once spent a short time in quarters.[12] After conquering the forest I once took the opportunity to visit my Hasiaika[13]. She then gave me a piece of bread and a cup of milk.

I hear that the lieutenant and battalion aide-de-camp who gave me so much trouble at Rai Gorodok was killed in the attack on the Christishche Forest between Majaki and the forester’s lodge. Peace to his ashes.

|

Editorial 1938 1939 1940 1941 1942 1943 1944 1945 1946 1947 1948 1949 Epilog Anhang |

|

January February March April May June July August September October November December Eine Art Bilanz Gedankensplitter und Betrachtungen Personen Orte Abkürzungen Stichwort-Index Organigramme Literatur Galerie:Fotos,Karten,Dokumente |

|

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. 26. 27. 28. 29. 30. 31. Erfahrungen i.d.Gefangenschaft Bemerkungen z.russ.Mentalität Träume i.d.Gefangenschaft Personen-Index Namen,Anschriften Personal I.R.477 1940–44 Übersichtskarte (Orte,Wege) Orts-Index Vormarsch-Weg Codenamen der Operationen im Sommer 1942 Mil.Rangordnung 257.Inf.Div. MG-Komp.eines Inf.Batl. Kgf.-Lagerorganisation Kriegstagebücher Allgemeines Zu einzelnen Zeitabschnitten Linkliste Rotkreuzkarte Originalmanuskript Briefe von Kompanie-Angehörigen |

- ↑ On 17 May at 22.10 hrs the 257th I.D. instructed the I.R.477 by radio message (KTB 257th I.D., NARA T-315 Roll 1805 Frame 001013 f.): “2nd battalion is at disposal again. Place one battalion at disposal of division in the evening.” The 2nd battalion had previously been divisional reserve. Due to the order, the 1st battalion was probably designated as a reserve the next day and positioned in a rear wooded area, where it is later mentioned twice: Day report of 19 May: “1st/J.R.477 unchanged in the forest south-eastwards Grünpunkt 100” (Frame 001030); divisional order of 21 May: “1st/J.R. 477 remains as divisional reserve in area Grün-Punkt 100” (Frame 001054)

- ↑ 29 May 1942: “Müller, Lt. u. Komp.Führer” (paybook p. 22)

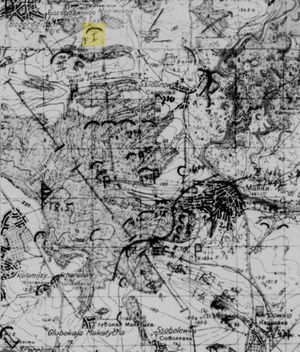

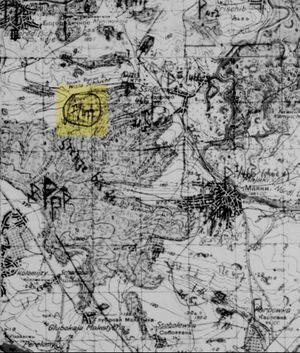

- ↑ Russland 1:100.000 sheet M-37 111-112 at MAPSTER

- ↑ KTB 257. I.D., NARA T-315 Roll 1805 Frame 001006

- ↑ KTB 257. I.D., NARA T-315 Roll 1805 Frame 001061

- ↑ 03:05 acc. to Benary p. 101. Upbeat of the grand summer offensive Case Blue/Operation Braunschweig towards the Caucasus (cf. KTB 257. I.D., NARA T-315 Roll 1805 Frame 001045). The attack “Fridericus” (I or South, respectively) was only executed by the southern wing (A.Gr. von Kleist (17th A. with XXXXIV A.K. and LII A.K.) and 1st Pz.A. with III Pz.K.) (Frame 000996) as the Soviets burst midway into the attack preparations of the northern wing (6th A.) with the Second Battle of Kharkov. The attack of the southern wing, brought forward on 17 May 1942, was in fact equivalently effective (KTB AOK 6 of 27 May 42, cited in a posting in Forum der Wehrmacht; cf. KTB OKW 1942 S. 366). On this also W. Russ p. 106 ff.

- ↑ Руки вверх! Hands up!

- ↑ Violation of Article 31 of the Geneva Convention Relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War, which, however, would be a war crime only in the case of coercion

- ↑ The description fits the Balka (ravine) Wissla, which also appears in the Division’s daily report (KTB 257. I.D., NARA T-315 Roll 1805 Frame 001003); however, the map lacks the mentioned stream.

- ↑ familiar to the author from his time in Hamburg; he had once wanted to become a merchant ship officer and had attended the seaman’s school in Hamburg-Finkenwärder for this purpose; during this time and during the voyage on the sail training ship “Padua” he also kept diary

- ↑ This tale always disgusted the author’s wife, especially because he also told it at table; however, he did not let it stop him, but at most affirmed that the dead man had been lying downstream from the place where he drank, downstream!

- ↑ cannot be arranged chronologically, at present

- ↑ Хазяйка, beloved