1946/November/6/en: Unterschied zwischen den Versionen

(Die Seite wurde neu angelegt: „{{Kalendernavigation}} {{Geoinfo | {{Geoo|Magazin 19: ''position still unknown''}} {{Geoo|Meadow area near the slaughterhouse}} {{Geok|https://www.google.de/…“) |

|||

| Zeile 11: | Zeile 11: | ||

6-8 November. The red {{wen|October Revolution}} was celebrated in a big way, as usual. For us it only meant increased guarding. | 6-8 November. The red {{wen|October Revolution}} was celebrated in a big way, as usual. For us it only meant increased guarding. | ||

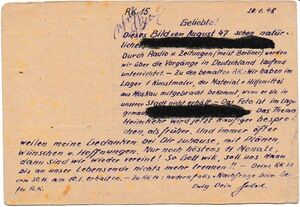

| − | [[File:1948-01-20_Buch_S_265a_Rotkreuzkarte.jpg|thumb|<span class="TgbT"></span>A censored [[Anhang/Tagebuch-Fotos/Rotkreuzkarte|Red Cross Postcard]] from Soviet captivity.<ref>This photocopy is the only example of its kind. All originals of the | + | [[File:1948-01-20_Buch_S_265a_Rotkreuzkarte.jpg|thumb|<span class="TgbT"></span>A censored [[Anhang/Tagebuch-Fotos/Rotkreuzkarte|Red Cross Postcard]] from Soviet captivity.<ref>This photocopy is the only example of its kind. All originals of the author’s postcards have been lost.</ref>]] |

Red Cross cards may now only contain 25 words. Of course, the text will be censored. Information about whereabouts, state of health (if poor), weight and anything negative is deleted (see picture). Disagreeable mail is simply thrown away. This work is also done by the Antifa comrades. Mail is only allowed from Germany and Austria. Mail from other countries is not handed over. The Antifa comrades cannot read foreign languages. I have written 11 times. Of these, 9 cards arrived at home. Delivery time up to half a year. | Red Cross cards may now only contain 25 words. Of course, the text will be censored. Information about whereabouts, state of health (if poor), weight and anything negative is deleted (see picture). Disagreeable mail is simply thrown away. This work is also done by the Antifa comrades. Mail is only allowed from Germany and Austria. Mail from other countries is not handed over. The Antifa comrades cannot read foreign languages. I have written 11 times. Of these, 9 cards arrived at home. Delivery time up to half a year. | ||

Bad workers are put into a special brigade. This brigade is given a norm that it must fulfil, otherwise the working hours are simply extended. This is forced labour. Extending working hours, shortening breaks, working outside at -40°''C'', using distrophic workers and countless other violations of the Geneva and Hague Conventions are the order of the day. | Bad workers are put into a special brigade. This brigade is given a norm that it must fulfil, otherwise the working hours are simply extended. This is forced labour. Extending working hours, shortening breaks, working outside at -40°''C'', using distrophic workers and countless other violations of the Geneva and Hague Conventions are the order of the day. | ||

| − | We have a larger group of Hungarians in the camp. They are sly fellows, lazy and cunning. When it's their turn to peel potatoes with us, they | + | We have a larger group of Hungarians in the camp. They are sly fellows, lazy and cunning. When it's their turn to peel potatoes with us, they don’t show up at first, until we finally fetch them after half an hour. And then they start peeling, cutting away so much potato with six short cuts that only a small cube remains. Our scolding doesn’t faze them. They finish their share as quickly as we do, but it results in at least one less bucket of potatoes. These wogs, however, don’t mind. They get on well with the population outside and are also more cunning at stealing than we are, so they always have plenty of extra rations. I think the congeniality between Hungarians and Russians is greater and therefore facilitates their contacts. |

| − | + | The atmosphere in the camp is unpleasant. There is the blind hatred of the “German” camp leadership against us officers. This also applies to some Landser. When I once reprimanded one of them in the washroom for splashing me, he grumbled, “You have nothing to say anymore!” On his way out, he meets a Russian recruit at the door and literally snaps his heels in front of him! That’s the German! - There is (apart from the hatred of some) the Russian’s lack of understanding of our mentality. It’s not always ill-intentioned, but it’s annoying. He is terribly suspicious and humourless. He forbids the currently popular hit song "Barcelona, du allein (you alone)..."<ref>[https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zLrkj0kLj1w Barcelona], 1943, [https://www.discogs.com/de/Willi-Stanke-Mit-Seinem-Orchester-Barcelona-Hei%C3%9Fe-Tage/release/3612644 music]: [https://www.discogs.com/de/artist/1218492-Franz-Wilczek Franz Wilczek], [http://www.45cat.com/record/1c0061471257 lyrics]: Inge Wolf</ref> because Spain is a [[w:en:Francoist_Spain|fascist dictatorship]]. When Opalev, an officer in the Russian camp headquarters, heard that we were fed up with captivity, he said he didn't understand! He drinks champagne like lemonade and cologne like schnapps. We are to eat as he does: dry bread with soup. (That's how the Russians eat it.) People with two suits are already capitalists, in his eyes. - There are the constant cheats on the rations. The potatoes have to be filled with a shovel instead of a fork so that as much sand as possible gets on the scales. Then he chases away the German rations officer, who is supposed to check the weighing, because he complained that Ivan had put his foot on the scales and put a stone on it. | |

| − | + | Red Cross cards are given every 4 weeks, according to regulations - but they are not enough for everyone! | |

| − | + | The wages, which are already manipulated downwards, are often not handed over. We are then told that it will be transferred to a blocked account and paid out when we are released! | |

| − | + | We get winter clothes, but in return they take away our green Wehrmacht coats. | |

| − | + | We are allowed to write letters, but they are often not forwarded. | |

| − | + | Our house has piped water, central heating and electricity, but it often doesn't work. | |

| − | + | And... and... and... | |

| − | In | + | In consistent implementation of socialist egalitarianism, women's equality is radically carried out in the Soviet Union (except in the Muslim states). Women do the same hard work as men. But the brigadiers of the women's brigades are mostly men. |

| − | ''' | + | '''Magazine 19'''. Cereals are stored in this warehouse. Large stacks of sacks full of potatoes, millet, flour and much else. More rarely, a few sacks of sugar or the like. Our work consisted of unloading the trucks that brought these goods here from the goods yard and loading other trucks that then took the stuff out again to the individual state-run shops in the city. There wasn’t too much to do. The Russian guards would sometimes slip away, and the Russian nachalnik wasn’t always present either. When we had the opportunity, of course, we put aside some of the rations for ourselves. Every experienced plenny is prepared for such occasions. The bags must always be tight and without holes. It is also useful to have a small bag with you at all times. At present, I always carry a tablespoon with a broken handle on this command. It is easy to store and you can use it to take a spoonful from an open flour sack and put it in your mouth, for example, as you pass by. If you had to do it by hand, you would soon have smeared your hand and mouth and would be betrayed. The fact that the flour sack is open is because it “accidentally” fell down during unloading and burst open. There are other methods, but you must not do it often, because the nachalnik is not stupid. |

| − | In | + | In another case at another command, we agreed with the supervisor beforehand: We wouldn’t steal anything (called “zappzerapp” in German-Russian gibberish), and in return he would give us something voluntarily at the end. But not all nachalniks were so philanthropic, and there was often a beating if you were caught in “zappzerapp”. There was a lot of stealing everywhere, by Russians and Germans. It was like an epidemic. One comrade even told me that German prisoners of war were lined up with machine pistols in front of a food magazine because the Russians were stealing too much. |

| − | + | Once we unloaded a goods wagon on a siding of the passenger station. Among the goods was a sack of sultanas. While one of us carried the heavy sack, I went sideways to help support the load. As I did so, I poked my finger into an existing hole to fish out a few sultanas. But the sultanas were a bit frozen and hard, so I broke my fingernails. It was hardly worth it for the few sultanas I managed to grab. Besides, this was a risky venture, because when loading such treasures, as with sugar, there are always a lot of watchdogs (who, by the way, are all hoping to get something for themselves). | |

| − | + | We stowed millet sacks in the large warehouse. From a sack that had opened, we filled our bags in unguarded moments. I had filled my haversack and went as inconspicuously as possible in front of the gate to put it in our truck standing there. Next to the truck stood our Mongolian guard. I wink at him and stow my bag in a corner. The Mongolian smiles. When we board the truck to go home after finishing our work, my bag is gone. The Mongol is still smiling, the scoundrel! | |

| − | Benno (von Knobelsdorff) | + | Benno (von Knobelsdorff) had a different method. He simply let the loose millet trickle into his felt boot, namely the right one. At the end of work, the guard suddenly had us line up and sit down. We had to take off our boots and turn them inside out. Benno took off the (empty) left one. The Ivan wants to see the other one too. Benno puts the left one back on and wants to stand up, but the Russian makes him sit down again. Benno sits down and takes off the left one again. The Ivan didn’t realise. So Benno moved into camp with a somewhat swollen right foot. |

| − | + | We loaded sacks of potatoes. In the meantime, we had set up a fireplace behind the warehouse, over which our mess kits filled with potatoes were hanging. But the storage supervisor discovers them just as we are about to check whether they are already cooked. Like an enraged bull, Ivan came running, kicking at the mess tins like a football so that they flew off in all directions. Then he tramples out the fire with both feet and lunges at Hans Sölheim, beating him like a savage. Hans turns around and runs away. The Russian behind him. The rest of us go back into the hall, somewhat depressed by the loss of our meal. While we are still standing together a bit perplexed, we hear a loud “Hello, Camerati!” from the hall entrance. We turn around and look in disbelief at Hans Sölheim and the nachalnik, both walking arm in arm towards us. They laugh and wave. Less than a minute ago the Russian was still furiously beating him, now he is holding him in his arms, laughing! That’s the Russian mentality! I have experienced such sudden changes of mood several times. They can be fatal if the Russian is drunk and armed.<ref>[[Anhang/Literatur#Cartellieri|Cartellieri]] p. 340 refers to the Russian concept of a “wide soul” ({{gerade|широкая натура}}).</ref> | |

| − | + | Behind the warehouse lies a long end of telephone wire. You can always use something like that, and I roll it up. Then I notice that it's too long and Hans Sölheim, who is next to me, says, “Why don’t you tear off a piece?” I do. In the evening in the camp he says to me: “You committed sabotage today,” and when I look at him uncomprehendingly he continues: “The wire was a telephone line. I had pulled it down before!” | |

| − | + | We '''unload peat trains at the western edge of town'''. The goods trains stop here and we simply throw the peat pieces down to the left and right onto the open meadowland. All with our hands, of course. Working with us is a brigade of convicted women and girls. When we complain that we have been imprisoned here for 2 years, they just laugh. 2 years is not a long time at all. After 5 years it would be hard, but 2 years? Nitchevo! | |

Dicht neben dem Gleis beginnt das eingezäunte Gelände eines Schlachthofes. Wir sehen, dass sich hin und wieder eine Tür öffnet und jemand herauskommt und wieder hineingeht. Mancher hat ja eine Nase dafür, wo es etwas zu holen gibt oder wo man etwas Essbares ergattern kann. So ein bisschen habe ich das auch schon gelernt. Also schlängele ich mich durch ein Loch in dem Drahtzaun an das Haus heran bis zur Tür. Hier brauche ich nicht lange zu warten. Aus der Tür tritt ein stämmiges Mädchen in blutbefleckter Gummischürze. Ich halte ihr schüchtern mein Kochgeschirr entgegen. Sie nimmt es mir wortlos aus der Hand und geht zurück. Nach kurzer Zeit kommt sie wieder und reicht mir mit unbewegtem Gesicht mein Kochgeschirr zurück, gefüllt mit frischem, warmem Blut. Ich verschwinde mit freundlichem Dank. Außerhalb des Schlachthofes, hinter der Halle, unterhalten wir ein Feuer, über dem wir das Blut gleich im Kochgeschirr erhitzen. Innerhalb weniger Minuten haben wir dann ein ganzes Kochgeschirr voller frischer Blutwurst. Manche nehmen es mit ins Lager, um es dort zu verkaufen. Ich habe später noch einmal auf diesem Schlachthof ein paar Tage gearbeitet, allerdings in dem Verwaltungsgebäude. Auch dort bekamen wir mittags in der Kantine ein Essen, saßen aber allein an einem Tisch, getrennt von den Russen. | Dicht neben dem Gleis beginnt das eingezäunte Gelände eines Schlachthofes. Wir sehen, dass sich hin und wieder eine Tür öffnet und jemand herauskommt und wieder hineingeht. Mancher hat ja eine Nase dafür, wo es etwas zu holen gibt oder wo man etwas Essbares ergattern kann. So ein bisschen habe ich das auch schon gelernt. Also schlängele ich mich durch ein Loch in dem Drahtzaun an das Haus heran bis zur Tür. Hier brauche ich nicht lange zu warten. Aus der Tür tritt ein stämmiges Mädchen in blutbefleckter Gummischürze. Ich halte ihr schüchtern mein Kochgeschirr entgegen. Sie nimmt es mir wortlos aus der Hand und geht zurück. Nach kurzer Zeit kommt sie wieder und reicht mir mit unbewegtem Gesicht mein Kochgeschirr zurück, gefüllt mit frischem, warmem Blut. Ich verschwinde mit freundlichem Dank. Außerhalb des Schlachthofes, hinter der Halle, unterhalten wir ein Feuer, über dem wir das Blut gleich im Kochgeschirr erhitzen. Innerhalb weniger Minuten haben wir dann ein ganzes Kochgeschirr voller frischer Blutwurst. Manche nehmen es mit ins Lager, um es dort zu verkaufen. Ich habe später noch einmal auf diesem Schlachthof ein paar Tage gearbeitet, allerdings in dem Verwaltungsgebäude. Auch dort bekamen wir mittags in der Kantine ein Essen, saßen aber allein an einem Tisch, getrennt von den Russen. | ||

Version vom 14. Oktober 2021, 14:58 Uhr

| GEO INFO | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magazin 19: position still unknown | ||||

| Meadow area near the slaughterhouse | ||||

| Buildings (of the Kalinin factory) | ||||

| Flax Combine | ||||

| Tileyard: position still unknown | ||||

| see also Localisation attempts and overview map | ||||

6-8 November. The red October Revolution was celebrated in a big way, as usual. For us it only meant increased guarding.

Red Cross cards may now only contain 25 words. Of course, the text will be censored. Information about whereabouts, state of health (if poor), weight and anything negative is deleted (see picture). Disagreeable mail is simply thrown away. This work is also done by the Antifa comrades. Mail is only allowed from Germany and Austria. Mail from other countries is not handed over. The Antifa comrades cannot read foreign languages. I have written 11 times. Of these, 9 cards arrived at home. Delivery time up to half a year.

Bad workers are put into a special brigade. This brigade is given a norm that it must fulfil, otherwise the working hours are simply extended. This is forced labour. Extending working hours, shortening breaks, working outside at -40°C, using distrophic workers and countless other violations of the Geneva and Hague Conventions are the order of the day.

We have a larger group of Hungarians in the camp. They are sly fellows, lazy and cunning. When it's their turn to peel potatoes with us, they don’t show up at first, until we finally fetch them after half an hour. And then they start peeling, cutting away so much potato with six short cuts that only a small cube remains. Our scolding doesn’t faze them. They finish their share as quickly as we do, but it results in at least one less bucket of potatoes. These wogs, however, don’t mind. They get on well with the population outside and are also more cunning at stealing than we are, so they always have plenty of extra rations. I think the congeniality between Hungarians and Russians is greater and therefore facilitates their contacts.

The atmosphere in the camp is unpleasant. There is the blind hatred of the “German” camp leadership against us officers. This also applies to some Landser. When I once reprimanded one of them in the washroom for splashing me, he grumbled, “You have nothing to say anymore!” On his way out, he meets a Russian recruit at the door and literally snaps his heels in front of him! That’s the German! - There is (apart from the hatred of some) the Russian’s lack of understanding of our mentality. It’s not always ill-intentioned, but it’s annoying. He is terribly suspicious and humourless. He forbids the currently popular hit song "Barcelona, du allein (you alone)..."[2] because Spain is a fascist dictatorship. When Opalev, an officer in the Russian camp headquarters, heard that we were fed up with captivity, he said he didn't understand! He drinks champagne like lemonade and cologne like schnapps. We are to eat as he does: dry bread with soup. (That's how the Russians eat it.) People with two suits are already capitalists, in his eyes. - There are the constant cheats on the rations. The potatoes have to be filled with a shovel instead of a fork so that as much sand as possible gets on the scales. Then he chases away the German rations officer, who is supposed to check the weighing, because he complained that Ivan had put his foot on the scales and put a stone on it.

Red Cross cards are given every 4 weeks, according to regulations - but they are not enough for everyone!

The wages, which are already manipulated downwards, are often not handed over. We are then told that it will be transferred to a blocked account and paid out when we are released!

We get winter clothes, but in return they take away our green Wehrmacht coats.

We are allowed to write letters, but they are often not forwarded.

Our house has piped water, central heating and electricity, but it often doesn't work.

And... and... and...

In consistent implementation of socialist egalitarianism, women's equality is radically carried out in the Soviet Union (except in the Muslim states). Women do the same hard work as men. But the brigadiers of the women's brigades are mostly men.

Magazine 19. Cereals are stored in this warehouse. Large stacks of sacks full of potatoes, millet, flour and much else. More rarely, a few sacks of sugar or the like. Our work consisted of unloading the trucks that brought these goods here from the goods yard and loading other trucks that then took the stuff out again to the individual state-run shops in the city. There wasn’t too much to do. The Russian guards would sometimes slip away, and the Russian nachalnik wasn’t always present either. When we had the opportunity, of course, we put aside some of the rations for ourselves. Every experienced plenny is prepared for such occasions. The bags must always be tight and without holes. It is also useful to have a small bag with you at all times. At present, I always carry a tablespoon with a broken handle on this command. It is easy to store and you can use it to take a spoonful from an open flour sack and put it in your mouth, for example, as you pass by. If you had to do it by hand, you would soon have smeared your hand and mouth and would be betrayed. The fact that the flour sack is open is because it “accidentally” fell down during unloading and burst open. There are other methods, but you must not do it often, because the nachalnik is not stupid.

In another case at another command, we agreed with the supervisor beforehand: We wouldn’t steal anything (called “zappzerapp” in German-Russian gibberish), and in return he would give us something voluntarily at the end. But not all nachalniks were so philanthropic, and there was often a beating if you were caught in “zappzerapp”. There was a lot of stealing everywhere, by Russians and Germans. It was like an epidemic. One comrade even told me that German prisoners of war were lined up with machine pistols in front of a food magazine because the Russians were stealing too much.

Once we unloaded a goods wagon on a siding of the passenger station. Among the goods was a sack of sultanas. While one of us carried the heavy sack, I went sideways to help support the load. As I did so, I poked my finger into an existing hole to fish out a few sultanas. But the sultanas were a bit frozen and hard, so I broke my fingernails. It was hardly worth it for the few sultanas I managed to grab. Besides, this was a risky venture, because when loading such treasures, as with sugar, there are always a lot of watchdogs (who, by the way, are all hoping to get something for themselves).

We stowed millet sacks in the large warehouse. From a sack that had opened, we filled our bags in unguarded moments. I had filled my haversack and went as inconspicuously as possible in front of the gate to put it in our truck standing there. Next to the truck stood our Mongolian guard. I wink at him and stow my bag in a corner. The Mongolian smiles. When we board the truck to go home after finishing our work, my bag is gone. The Mongol is still smiling, the scoundrel!

Benno (von Knobelsdorff) had a different method. He simply let the loose millet trickle into his felt boot, namely the right one. At the end of work, the guard suddenly had us line up and sit down. We had to take off our boots and turn them inside out. Benno took off the (empty) left one. The Ivan wants to see the other one too. Benno puts the left one back on and wants to stand up, but the Russian makes him sit down again. Benno sits down and takes off the left one again. The Ivan didn’t realise. So Benno moved into camp with a somewhat swollen right foot.

We loaded sacks of potatoes. In the meantime, we had set up a fireplace behind the warehouse, over which our mess kits filled with potatoes were hanging. But the storage supervisor discovers them just as we are about to check whether they are already cooked. Like an enraged bull, Ivan came running, kicking at the mess tins like a football so that they flew off in all directions. Then he tramples out the fire with both feet and lunges at Hans Sölheim, beating him like a savage. Hans turns around and runs away. The Russian behind him. The rest of us go back into the hall, somewhat depressed by the loss of our meal. While we are still standing together a bit perplexed, we hear a loud “Hello, Camerati!” from the hall entrance. We turn around and look in disbelief at Hans Sölheim and the nachalnik, both walking arm in arm towards us. They laugh and wave. Less than a minute ago the Russian was still furiously beating him, now he is holding him in his arms, laughing! That’s the Russian mentality! I have experienced such sudden changes of mood several times. They can be fatal if the Russian is drunk and armed.[3]

Behind the warehouse lies a long end of telephone wire. You can always use something like that, and I roll it up. Then I notice that it's too long and Hans Sölheim, who is next to me, says, “Why don’t you tear off a piece?” I do. In the evening in the camp he says to me: “You committed sabotage today,” and when I look at him uncomprehendingly he continues: “The wire was a telephone line. I had pulled it down before!”

We unload peat trains at the western edge of town. The goods trains stop here and we simply throw the peat pieces down to the left and right onto the open meadowland. All with our hands, of course. Working with us is a brigade of convicted women and girls. When we complain that we have been imprisoned here for 2 years, they just laugh. 2 years is not a long time at all. After 5 years it would be hard, but 2 years? Nitchevo!

Dicht neben dem Gleis beginnt das eingezäunte Gelände eines Schlachthofes. Wir sehen, dass sich hin und wieder eine Tür öffnet und jemand herauskommt und wieder hineingeht. Mancher hat ja eine Nase dafür, wo es etwas zu holen gibt oder wo man etwas Essbares ergattern kann. So ein bisschen habe ich das auch schon gelernt. Also schlängele ich mich durch ein Loch in dem Drahtzaun an das Haus heran bis zur Tür. Hier brauche ich nicht lange zu warten. Aus der Tür tritt ein stämmiges Mädchen in blutbefleckter Gummischürze. Ich halte ihr schüchtern mein Kochgeschirr entgegen. Sie nimmt es mir wortlos aus der Hand und geht zurück. Nach kurzer Zeit kommt sie wieder und reicht mir mit unbewegtem Gesicht mein Kochgeschirr zurück, gefüllt mit frischem, warmem Blut. Ich verschwinde mit freundlichem Dank. Außerhalb des Schlachthofes, hinter der Halle, unterhalten wir ein Feuer, über dem wir das Blut gleich im Kochgeschirr erhitzen. Innerhalb weniger Minuten haben wir dann ein ganzes Kochgeschirr voller frischer Blutwurst. Manche nehmen es mit ins Lager, um es dort zu verkaufen. Ich habe später noch einmal auf diesem Schlachthof ein paar Tage gearbeitet, allerdings in dem Verwaltungsgebäude. Auch dort bekamen wir mittags in der Kantine ein Essen, saßen aber allein an einem Tisch, getrennt von den Russen.

Wir bauen ein zerstörtes Gebäude (des Textilkombinats?[4]) wieder auf. Das dreistöckige Haus ist schon bis zum Dachstuhl fertig. Nur der Dachstuhl und einige kleinere Maurerarbeiten sind noch zu machen. Ich bin Brigadier der Hilfsarbeiterbrigade. Wir schleppen die Backsteine, immer 3–4 Stück, auf der Schulter zu Fuß 3 Stockwerke hinauf. Eine Schinderei, aber wir lassen es so langsam wie möglich gehen. Der Natschalnik ist ein Ekel. Da er keine Uhr besitzt, erkundigt er sich immer bei mir nach der Uhrzeit. Aber obgleich ich ihm immer die korrekte Zeit angebe, lässt er uns immer 1/4 Stunde länger arbeiten, weil er natürlich wieder vermutet, dass ich ihn belüge. Die Folge ist, dass wir ihn nun wirklich betrügen, und zwar nicht nur mit der Uhrzeit. Da er uns auch nicht von der eingezäunten Arbeits••• S. 311, 2 Bilder •••stelle fortlässt (was allerdings auch nicht gestattet ist), so schleiche ich mich öfter heimlich weg. Zwar brauche ich als Brigadier nicht mitzuarbeiten, aber von der Arbeitsstelle darf ich mich nicht entfernen.

Das Nebengebäude ist ebenfalls dreistöckig. Da die Trennwand zwischen beiden Häusern im Dachgeschoss noch nicht gemauert ist, kann man ohne weiteres auf den Dachboden des Wohnhauses hinübersteigen. Das tat ich ’mal, um mich umzusehen. Hier liegt auf der Bretterlage des Dachbodens eine 10 cm dicke Schlackeschicht. Aber die Bodenbretter sind nicht dicht, und durch die Ritzen kann ich in die Küche hinuntersehen, wo die Hausfrau gerade am Herd herumhantiert. Ich wundere mich, dass sie das leise Rieseln der Schlacke nicht bemerkt, die durch die Ritzen auf dem Küchenfußboden fällt. Oder ist sie es gewöhnt?

Ich habe ein paar Bretter geklaut und steige wieder über den Dachboden des Nachbarhauses in den dortigen Treppenflur. Hier klopfe ich, im 3. Stock beginnend, an jede Wohnungstür und biete meine Bretter zum Mindestpreis an, als Sonderangebot. Aber niemand will sie haben. Sie bekommen wohl zuviel solcher Angebote. Schließlich erbarmt sich eine Frau im 1. Stock und gibt mir 4 Kartoffeln dafür.

Ein paar Tage später versuche ich es noch einmal mit einem 2 m langen Rundholz von 15 cm Durchmesser. Diesmal laufe ich aber, immer in Deckung, über den Hof zum nächsten Häuserblock hinüber. Aber auch hier werde ich überall abgewiesen. Ich muss den Balken einfach im Hausflur stehen lassen.[5]••• S. 311: Haupttext unterbrochen •••

••• S. 312: Haupttext fortgesetzt •••Hans hatte unweit von dem Fotogeschäft einen Tabakladen entdeckt, nur 100 m weiter in derselben Straße. Dort gab es sehr preiswerte Zigaretten und billigen Tabak. Er behielt dieses Geheimnis für sich und machte im Lager mit einem kleinen Preisaufschlag ein gutes Geschäft. Als er dann erkrankte, weihte er mich in das Geheimnis ein und beschrieb mir die Lage des Ladens. Nun holte ich die Ware von dort, und zwar immer gleich einen Rucksack voll. Einmal dauerte es etwas länger, bis ich die zahlreichen Päckchen im Rucksack verstaut und mit der Frau abgerechnet hatte. Inzwischen hatte sich eine Schlange von 6–7 Personen gebildet. Aber sie sagten kein Wort und warteten geduldig, bis ich fertig war, obgleich sie mich sicher als Kriegsgefangenen erkannt hatten.

Im Lager hat der Hans einen Landser, der für ihn die Zigaretten verkaufte, gegen 50% Beteiligung. Ich wollte alles allein verdienen und selbst verkaufen. Und während Hans auf seiner Pritsche lag und ruhte, raste ich im ganzen Lager herum, um meine Zigaretten zu verkaufen. Hans hatte seinen gesamten Bestand verkauft, ich dagegen war nicht eine einzige Packung los geworden. Ich bin eben kein Kaufmann. Dann machte ich einen noch größeren Fehler. Ein cleverer Kamerad hatte Hans’ Zigarettenverkäufer beobachtet. Er machte sich an mich heran, und ich erzählt ihm in meiner Harmlosigkeit von dem Laden und nahm ihn eines Tages sogar mit, nachdem er mir heuchlerisch erklärt hatte, dass er an Geschäftemachen überhaupt nicht interessiert sei. Seitdem schnappt uns dieser Gauner durch Großeinkäufe alles weg und hat uns das ganze Geschäft verdorben. Hans hat mir diese meine Dummheit nie verziehen. Seitdem ist unsere Freundschaft merklich abgekühlt.

Flachskombinat.[6] Da ich gerade von meiner Dummheit rede: Hier gleich noch eine, die ich im Flachskombinat begangen habe. Wir arbeiteten hier oft auch in der Nähe der Küche und versuchten natürlich, dort etwas zu essen zu bekommen. In der Küche arbeiteten eine ganze Anzahl von Mädchen unter der Leitung eines Kochs. Den Mädchen war selbstverständlich – wie auch der ganzen Bevölkerung – jeglicher Kontakt mit uns verboten. Dennoch steckten die Küchenmädchen uns gelegentlich etwas zu. Eines Tages hatten sie mir eine ganze Portion Mittagessen zugeschoben. Nachdem ich sie hinter einem Wandschirm ausgelöffelt hatte, ging ich arglos mit meinem leeren Teller an die Theke und übergab ihn einem der Mädchen mit einem lauten „bolschoi sspassiba[7]!“ Das Mädchen wirft einen schnellen Blick zu dem Koch, ihrem Natschalnik, sieht mich dann vorwurfsvoll an und nimmt mir wortlos den Teller ab. Der Koch tat, als hätte er nichts gehört. Ich verschwand jedenfalls schnellstens aus der Kantine. Ich Idiot!

In einem Raum neben der Küche war eine Nähstube, in der etwa 10 Mädchen beschäftigt waren. Hier tauchte Günter Heuer öfter auf. Jungenhaft und fröhlich kam er herein gewirbelt, kauderwelschte auf Russisch mit den Mädchen, dass sie sich vor Lachen schüttelten. Er war sicher ihr Schwarm.

Hinter der Küche lag ein Abfallhaufen, auf dem ich einen noch frische kleine Mohrrübe entdecke. Ich hebe sie auf, wische sie ab und esse sie auf. Darüber habe ich mich noch lange geärgert. So weit bin ich denn doch nicht gesunken, dass ich von einem Abfallhaufen fressen muss.

Ziegelei. Sie lag ziemlich weit außerhalb der Stadt auf einer breiten, flach gewölbten Hochfläche, frei und offen in baumlosem Gelände. Sie war im Kriege zerstört worden und soll wieder aufgebaut werden. Der Weg dorthin führt über die kahle Hochfläche. Der ungewöhnlich kalte Winter bläst uns den eisigen Wind durch unsere Kleidung, dass wir bis ins Mark erschauern. Wenn wir einmal stehen bleiben müssen, fürchten wir zu erfrieren. Schon der An- und Abmarsch ist eine Quälerei, und die Arbeit auf dieser windigen Höhe ist hart. Wir mauerten und mischten Mörtel bei –20°, denn der russische Ingenieur musste sein Plansoll erfüllen: Laut Plan sollte die Produktion ••• S. 313 •••im Frühjahr anlaufen. Also wird trotz der Kälte einfach weiter gemauert, und wenn nicht genügend Steine herankamen, rissen wir die unteren Lagen der meterdicken Ringmauer des Ofens ab und mauerten sie oben wieder drauf. Es ist unglaublich, aber der Ingenieur hatte nur ein Ziel: Er musste seine Norm erfüllen, seinen Terminplan einhalten, denn im Frühjahr muss die Produktion anlaufen. Wenn dann etwas schief ging, war es nicht mehr seine Sache. Er hatte sein Plansoll erfüllt.

Auf der Ziegelei arbeiten etwa 100 Mann. Das Kommando war äußerst unbeliebt und gefürchtet, denn es gab viele Ausfälle durch Erkrankungen, Erkältungen und Erfrierungen.

|

Editorial 1938 1939 1940 1941 1942 1943 1944 1945 1946 1947 1948 1949 Epilog Anhang |

|

January February March April May June July August September October November December Eine Art Bilanz Gedankensplitter und Betrachtungen Personen Orte Abkürzungen Stichwort-Index Organigramme Literatur Galerie:Fotos,Karten,Dokumente |

|

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. 26. 27. 28. 29. 30. 31. Erfahrungen i.d.Gefangenschaft Bemerkungen z.russ.Mentalität Träume i.d.Gefangenschaft Personen-Index Namen,Anschriften Personal I.R.477 1940–44 Übersichtskarte (Orte,Wege) Orts-Index Vormarsch-Weg Codenamen der Operationen im Sommer 1942 Mil.Rangordnung 257.Inf.Div. MG-Komp.eines Inf.Batl. Kgf.-Lagerorganisation Kriegstagebücher Allgemeines Zu einzelnen Zeitabschnitten Linkliste Rotkreuzkarte Originalmanuskript Briefe von Kompanie-Angehörigen |

- ↑ This photocopy is the only example of its kind. All originals of the author’s postcards have been lost.

- ↑ Barcelona, 1943, music: Franz Wilczek, lyrics: Inge Wolf

- ↑ Cartellieri p. 340 refers to the Russian concept of a “wide soul” (широкая натура).

- ↑ möglicherweise die Häuser der Fabrik „Kalinin“ an der Witebsker Chaussee 46–50, die in genau dieser Zeit von Deutschen erbaut wurden (Mitteilung von Anna Shukowa auf Facebook)

- ↑ Die im Original hier anschließenden Absätze "Photomaton" und "Ostern/Friedhofsbesuche" wurden unter den zutreffenen Daten 8./12.46 bzw. 14./4.47 gespeichert.

- ↑ An der Stelle des damaligen Textil- oder Flachskombinats steht jetzt das Einkaufszentrum „Galaktika“.

- ↑ большое спасибо, großen Dank!